Orwell Subverted

The CIA and the Filming of Animal Farm

Daniel J. Leab

“What emerges in this book is a fascinating study of the complex relationship between the political and cultural imperatives that go into the shaping of a single film. It is difficult to see any other account displacing Leab’s as the definitive historical account of its production and reception. There are many monographs on individual films, but few that demonstrate this level of detail.”

- Description

- Reviews

- Bio

- Table of Contents

- Sample Chapters

- Subjects

Recently, a number of works have been written—notably, those by Frances Stoner Saunders and Tony Shaw—that make reference to the underlying governmental control surrounding Animal Farm. Yet there is still much speculation and confusion as to the depth of the CIA’s interference. Leab continues where these authors left off, exploring the CIA’s dominant hand through extensive research and by giving fascinating details of the agency’s overt and subtle influences on the making of the film. Leab’s thorough investigating makes use of sources that have been excluded in past accounts, such as CIA papers retrieved through the Freedom of Information Act and material from the Orwell Archive. He also incorporates the testimonials of animators John Halas and Joy Batchelor and, most significantly, the previously unexplored archive documents of Animal Farm producer Louis de Rochemont.

“What emerges in this book is a fascinating study of the complex relationship between the political and cultural imperatives that go into the shaping of a single film. It is difficult to see any other account displacing Leab’s as the definitive historical account of its production and reception. There are many monographs on individual films, but few that demonstrate this level of detail.”

“A first-rate book. Orwell Subverted breaks entirely new ground in its thorough treatment of the role of the American filmmaker Louis de Rochemont in the story of the filming and distribution of Animal Farm.”

“The book has all the suspense of a thriller, though the final chapter lacks that genre’s satisfactory tying off of all loose ends. Nevertheless, this is such a thorough, convincing, and entertaining telling of its chosen tale that it seems unlikely to be readily superseded.”

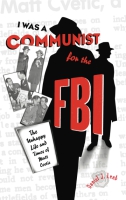

“Leab, editor of the journal American Communist History and author of I Was a Communist for the FBI and many articles on Hollywood’s Cold War films, knows this period well. His thorough research uncovered correspondence and financial information in archives in both the United States and England that allowed him to compile the most complete account to date of the film’s production.”

Daniel J. Leab is Professor of History at Seton Hall University. He is the author of several books, including I Was a Communist for the FBI: The Unhappy Life and Times of Matt Cvetic (Penn State, 2000).

Contents

Foreword by Peter Davison, OBE

Preface

Acknowledgments

1. Orwell and Animal Farm

2. OPC, the Sponsoring Agency

3. The Producer, Louis de Rochemont

4. Genesis, and Getting Right with Sonia Orwell

5. The Animators, Halas and Batchelor

6. Creating Animal Farm, the Movie

7. Envisioning a Politically Correct Film Version of Animal Farm

8. The Politics of Filming Animal Farm

9. Finalizing a Politically Correct Film Version of Animal Farm

10. Reception of the Film

11. The Afterlife of the Film and Its Creators

12. Propaganda and Propagandists

Notes

Bibliography

Index

1

Orwell and Animal Farm

The CIA was attracted to George Orwell because of his political slant and antitotalitarian novels. Orwell had become an icon of the anti-Soviet, anti-Stalinist Left. His friend George Woodcock, the anarchist pacifist critic, later recalled that by 1948 one could “ask any Stalinist what English writer is the greatest danger to the Communist cause, and he is likely to answer George Orwell.” For Woodcock and many others, Animal Farm (first published in the United Kingdom in 1945 and in the United States a year later) played a significant role in establishing Orwell’s anti-Communist reputation.

Justly described as the most famous allegory of the twentieth century, Animal Farm certainly exhibited an anti-Soviet animus and clearly was hostile to Stalin. According to Orwell, “this book was first thought of, so far as the central idea goes, in 1937.” He had gone to Spain to fight the Fascists who had risen against the legitimate democratic government of that country. The Communists, under the supervision of the Soviets, had assumed control of that government and forcibly suppressed the left-wing forces Orwell had joined and fought with against the Fascists. He had to flee Spain to save his life. His experience in Spain informed his anti-Communism and his view of the Soviet Union as totalitarian. The genesis of Animal Farm lay in his desire, “upon my return from Spain,” to expose “the Soviet myth in a story that could be easily understood by anyone.”

While the main outlines of the book were clear in Orwell’s mind for several years, he did not begin writing it until November 1943. The author-translator Michael Meyer, then in his early twenties and a new friend of Orwell’s, recalls him describing Animal Farm as a “kind of parable, about people . . . blind to the dangers of totalitarianism, set on a farm where the animals take over.” John Rodden asserts that the “point of departure for Orwell’s fable was a statement from Karl Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844: ‘The worker . . . no longer feels himself . . . anything but animal. What is animal becomes human and what is human becomes animal.’” It struck Orwell that “men exploit animals in much the same way as the rich exploit the proletariat,” and he proceeded to analyze Marxian theory from that point of view.

Orwell had finished a draft of what has sometimes been called his “animallegory” by the end of February 1944. In March he wrote his publisher, the fellow-traveling Victor Gollancz, about the book, which he described as “anti-Stalin” and as “a fairy story” with political meaning, of only about thirty thousand words (the book was less than a hundred pages when finally published). A tentative Orwell sent a copy of the manuscript to Gollancz, although he thought it was not “the kind of thing that you would print.” In the 1930s Gollancz had taken what proved to be a costly chance on Orwell the indifferent novelist, whose books did not sell. One critic called them “stories of defeat.” The militantly leftist publisher had passed on Orwell’s anti-Stalinist Spanish Civil War reportage (Homage to Catalonia), and he now did likewise with Animal Farm, reporting to Orwell’s agent that the firm “could not possibly publish a general attack of this nature.”

That attack certainly impeded publication of the book. It was not just the “left-wing carriage trade” (to use Dame Rebecca West’s pungent phrase) that proved hostile to Animal Farm. In wartime Britain the establishment was firmly committed to that country’s Soviet ally in the struggle against Nazi Germany. The average citizen was full of admiration for the hard-fought success of the Red Army on the eastern front, and referred affectionately to Stalin as “Uncle Joe.” The publisher Frederic Warburg later referred to “the Communist influenza that ravaged so many households.” The year 1944 has rightly been called the “most inappropriate moment possible” to try to publish a thinly camouflaged attack on Stalin and the Soviet Union.

Gollancz was far from alone in his unwillingness to publish such a book. T. S. Eliot, in his capacity as a senior editor at the British firm of Faber & Faber, wrote a letter of rejection with what has been termed “Jesuitical courtesy”; while commending Orwell for his distinguished writing and clever handling of the fable, Eliot concluded regretfully, “we have no conviction . . . that this is the right point of view from which to criticize the political situation at the present time.” The manuscript also encountered more sinister forces. The respected publisher Jonathan Cape, reported to be initially keen on the manuscript, bowed out after consulting an “important official” at the Ministry of Information, who advised against publication. The official is presumed to be Peter Smollett, who during the war headed the ministry’s Russian section, earning an OBE for his services to the Crown. He may also have served another master, for he was thought to be a Soviet agent and, according to a Russian spymaster, was controlled by the same man to whom such Soviet spies as Kim Philby reported. Smollett’s family has vigorously denied suggestions that he was a spy. Born Hans Peter Smolka in Vienna in 1912, he wrote pro-Soviet travel journalism for various UK outlets during the 1930s, became a naturalized British subject in 1938, changed his name, and after the war’s outbreak joined the Ministry of Information, where he energetically organized pro-Soviet propaganda and suppressed “unfavorable comment” on Stalinist Russia.

A concerned and depressed Orwell, fuming about Cape’s “intellectual cowardice” and acutely aware of the opposition to the book, at one point considered publishing it himself. In late July 1944, however, Secker & Warburg, which in 1938 had published Homage to Catalonia, agreed to bring out Animal Farm, even though the earlier book had proved “a bad risk,” in Orwell’s words. The last of the fifteen hundred copies that made up the first UK edition were not sold until 1951, according to Peter Davison. But Warburg was not put off by these meager results or by Animal Farm’s political implications, and despite what he recalled as strong opposition within the firm and from his family, he carried the day—Secker & Warburg published Animal Farm.

In 1936 Warburg, not yet forty, borrowed £;5,000 from a well-off relative to buy out Martin Secker and establish a new imprint. Over the years Warburg built up a wide-ranging, respected, and important list of authors, including André Gide, Franz Kafka, and Thomas Mann. The firm quickly gained a substantial reputation for “publishing books from a Left viewpoint that had been turned down elsewhere,” which led some critics to dub Warburg a “Trotskyite publisher.” At his eightieth birthday dinner Warburg declared that, his other successes notwithstanding, Animal Farm “made me as a publisher.”

Because of wartime paper rationing in the United Kingdom, Secker & Warburg was short the paper needed for printing Orwell’s book, and it went on sale formally only on August 17, 1945, just days after the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan and ended World War II. Because of Animal Farm’s political stance, the book became part of the postwar debate about the future of the peace. That debate notwithstanding, the book received fine reviews overall and was out of print in a matter of days. A second impression of ten thousand copies, more than twice the original printing, appeared some three months later, and it also sold extremely well. It has never been out of print since then.

Orwell was not unknown in some American literary circles. His contributions to journals such as Partisan Review and Commentary (he appeared in its first issue) won him admirers in the United States. Orwell’s “London Letter” column (he wrote fifteen for Partisan Review between 1941 and 1946), according to one historian of that publication, was particularly important to the journal’s evolution. And a New Republic critic wrote in September 1946 that the news that “Orwell had written a satirical allegory telling the story of a revolution by farm animals . . . was like the smell of a roast from a kitchen ruled by a good cook, near the end of a hungry morning.”

Still, despite its enormous commercial success in the United Kingdom, Animal Farm had a hard time finding an American home. Orwell had anticipated this, writing his agent, “I don’t fancy it will be easy to find an American publisher for this book.” Suggestions and recommendations from American friends led nowhere. Warburg’s assertion that there were “twelve or more rejections” has been questioned by Crick, who nonetheless believes that certainly there were “a lot.” Some of the rejections were straightforward, made on the grounds that the book was “too short for adequate marketing.” At least one rejection was patently foolish: Orwell reported to a New York correspondent that the Dial Press “rejected it on the ground that ‘the American public is not interested in animals’ (or words to that effect).”

Orwell (and some of his supporters) were aware that, as in the United Kingdom, some American publishers had rejected Animal Farm on political grounds. Partisan Review editor Philip Rahv, who considered himself a great admirer, warned Orwell in January 1946 that a lot of left-wing opinion in the United States was “almost solidly Stalinist.” There is some basis for historian and polemicist Peter Viereck’s charge that Orwell’s book suffered because of “the brilliantly successful infiltration of Stalinoid sympathizers in the book world.” Historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. remembers returning from wartime service in Europe with copies of Animal Farm, which had enchanted him; he attempted to interest his American publisher, but the firm quickly turned it down because, intimates Schlesinger, the editor-in-chief was “a defender of Stalinism.”

In any event, the book’s commercial success in the United Kingdom led to its publication in the United States by Harcourt, Brace. Frank Morley, an editor there who had worked for Faber & Faber before the war, visited England in the fall of 1945 to scout the book trade. In a Cambridge bookshop he encountered customers seeking to purchase the sold-out Animal Farm. He managed to get a copy, and he made a deal in January 1946 to publish the book in the United States. On returning home his deal, as he recalled, received “a far from enthusiastic reception” from his colleagues, an attitude that changed dramatically when Orwell’s book became a Book-of-the-Month Club selection in September 1946.

The Book of the Month Club News enthusiastically endorsed the book, recommending it to its members as “one of the great political satires.” This review was written by the popular writer and critic Christopher Morley, brother of the man who had acquired the book for Harcourt, Brace and a member of the club’s board of editors since its organization in 1926. Another member of the selection committee called Animal Farm “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of our time.” And Harry Scherman, the club’s president, recommended that subscribers “pick Animal Farm rather than any other alternative Club choice”; for him Orwell was a “fearless individual” who spoke “for the people of a troubled time” through a “little gem of an allegory.” Such endorsements, and a plethora of favorable reviews, helped the club sell more than 450,000 copies between 1946 and 1949, when a “dirty tricks” section of the CIA undertook to create a film version.

Harcourt had released the book in August 1946 and, like the Book-of-the-Month Club, experienced terrific sales. Animal Farm was a publishing sensation. A few reviewers, mostly on the Left, were, Orwell noted, “not very friendly.” The New Republic’s critic found the book “dull,” the allegory a “creaking machine” that consisted of “stereotyped ideas.” The Nation’s reviewer found the book “troublesome” and “inadequate,” concluding that “its political relevance is more apparent than real.” As might be expected, the Communist-controlled New Masses savaged the book and its author, who was said to have a “warped fascist-Trotskyite mind” that seethed with hatred.

Happily, the favorable reviews far outweighed the negative. The influential critic Edmund Wilson lauded the book in the New Yorker as “absolutely first rate” and praised Orwell as “one of the ablest and most interesting writers that the English have produced in this period.” A reviewer in the iconoclastic left-wing journal Politics found the book “amusing” and “brilliant,” correctly gauging that it would “infuriate all those who believe in Stalinism.” Surprisingly, Vogue, the stylish fashion magazine, ran an engaging profile of Orwell, which, in discussing Animal Farm, trenchantly concluded that much of the book’s “success comes from its fortunate choice of . . . subject . . . , the policies and philosophies of Soviet Russia,” about which the book, it was said, is as “pointed as a pin.”

No reader, then or now, with even a smattering of knowledge of Soviet history from 1917 to 1944 could miss Orwell’s obvious targets. Orwell’s “code,” as John Rodden has put it, is easy to crack. Using animal figures, the book sketches various aspects of that unhappy history, and does so, as a fascinated American reviewer wrote, in a way that raises “goose pimples.” The parallels drawn by the book are not always exact, and some of Orwell’s more arcane points may now be lost on readers not well versed in Soviet history, as for example his analogy between the pigs’ appropriation of milk and apples for their own use and the crushing of the 1921 Kronstadt revolt against the Bolsheviks by former supporters disheartened by the policies of the newly established Communist state. But with regard to the main characters and events there can be no doubt.

The revolt of the animals at Manor Farm against Farmer Jones is Orwell’s analogy with the October 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. The assistance Jones receives from neighboring farmers in his attempt to regain control of what the animals have renamed Animal Farm is equivalent to the Western powers’ efforts in 1918–21 to crush the Bolsheviks. Animal Farm’s symbolic hoof and horn are the hammer and sickle. The pigs’ ascent to power mirrors the rise of a Stalinist bureaucracy at the expense of everybody else. The ruthless and tyrannical boar, Napoleon, who emerges as the farm’s sole leader, is Stalin. And Trotsky’s counterpart, the pig Snowball, his valuable contributions to Animal Farm notwithstanding, falls prey to Napoleon/Stalin, and remains a scapegoat in exile and after his death. The painful efforts of the animals to build the windmill recall the various Five Year Plans, which industrialized the USSR at great human cost. The puppies taken over by Napoleon, who become his fierce enforcers, are the secret police. The pigs’ deplorable treatment of the other animals echoes the internal terror faced by Soviet citizens during the 1930s. Indeed, as Orwell biographer Jeffrey Meyers points out, “virtually every detail has political significance in this allegory.”

The end of the book (a noisy, somewhat fragile and contentious rapprochement between pigs and men) reflected Orwell’s view of the 1943 Teheran Conference between Stalin and the leaders of his World War II allies, American president Franklin D. Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston Churchill. “Everybody,” Orwell later recorded, thought the conference “had established the best possible relations between the USSR and the West,” but, as he noted, these relations had deteriorated, and, as he presciently predicted, they would continue to unravel.

Some critics argued, and still do, that Animal Farm was more than just an attack on Stalinism and the Soviet state. In their view the book’s target is totalitarianism of any stripe, including that practiced by capitalist states. These critics point to Orwell’s self-proclaimed Socialism and his contempt for what he called “the ordinary stupid capitalist.” By their lights Orwell remained committed to Socialism until his death in 1950, even as he “became extremely frustrated with both the follies of left wing intellectuals in Britain and the limited achievements of the Labor government” after its election in 1945.

It is true enough that neither the Labor government in the United Kingdom nor the Russian Revolution per se was Orwell’s sole target. In explaining his purpose in writing Animal Farm, Orwell made it clear that he meant for the book to have “wider application.” He wrote Dwight Macdonald that his target was “violent conspiratorial revolution, led by unconsciously power hungry people.” For Orwell, “that kind of revolution . . . can only lead to a change of masters.” Benevolent dictatorship, as far as Orwell was concerned, was an oxymoron.

Certainly Orwell never forgot his Socialist roots. For all his condemnation of Stalin’s brand of Marxism (which he made very clear: “I hate the Stalin regime”), Orwell wanted people to realize that they must build their own Socialist movement, and he expected democratic Socialism in the West to exert a “regenerative influence.” Orwell knew he lived in “an evil time,” but he never lost his passion for social justice. For Orwell, as many have argued, the story of the animals serves as a warning about a stratified society without limitations.

Moreover, for all Animal Farm’s anti-Stalinism, it is worth remembering that the book still celebrates the Soviet defeat of the powers that wished to crush the Bolsheviks and the state that they created. The farm animals, moreover, after defeating Farmer Jones and his allies, work together harmoniously for a time. They enjoy life on the farm, and their condition improves significantly despite numerous severe hardships, before Napoleon and his pigs take over.

Orwell, a keen and thoughtful critic, was not condemning “the benevolent intentions of Socialism” but the tendency of nearly any utopian movement to lead to the “extinction of individuality, culture, and emotion.” Although the fact seems obvious, we must not lose sight of Orwell’s own Socialism. The historian Ben Pimlott, having reviewed much of Orwell’s writing, unequivocally states that we must remember that “Orwell was a Socialist.” And Pimlott forcefully and convincingly argues that this point needs underlining, “for there are many who have preferred to ignore this fundamental aspect of his life and work.”

A good example is C. M. Woodhouse’s introduction to a 1956 American paperback edition of Animal Farm. Woodhouse praises Orwell for his political insights and acumen and quotes one of Orwell’s more famous essays (“Why I Write”): “Every line I have written since 1936 has been against totalitarianism.” As John Rodden points out, however, Woodhouse leaves off the end of the sentence, which continues, “and for democratic socialism.”

Monty Woodhouse, who bowdlerized Orwell, was an eminent historian, decorated war hero, Conservative MP, successful business executive, and a man, in the words of one historian, with “a secret service past” (he had served British intelligence as a “station chief” in the Middle East). His shortening of Orwell’s sentence is an act of deception and distortion designed to adapt Orwell’s book to a particular point of view.

Like Woodhouse, the CIA personnel involved in making Animal Farm into a propaganda film may have found aspects of Orwell and his book less than palatable. But they ignored these inconvenient aspects of the man’s politics and proceeded as if Orwell’s target was Soviet totalitarianism, pure and simple. Certainly it was clear to them, and to others involved in producing the film, that Orwell’s parable was all about Stalinism and the USSR. They saw no complexity, no duality of view, and, like Woodhouse, certainly no Socialist vision. What interested them was Orwell’s stated intention of “exposing the Soviet myth in a story that could be easily understood by almost anyone,” his having written what Orwell himself described as “a satirical story against Stalin.”

What the writer Timothy Garton Ash has dubbed “the Orwell effect” had a powerful impression and lasting impact on these people, as it has had on anticommunists ever since the publication of the book. The CIA people saw Animal Farm as a detailed, powerful, convincing “allegory of corruption, betrayal, and tyranny in Communist Russia”—one that would serve well and effectively as a “propaganda weapon.” The film version was but one aspect of the American government’s cultural offensive in the heyday of the Cold War, an offensive integral to a number of U.S. policies and strategies.

Also of Interest

Mailing List

Subscribe to our mailing list and be notified about new titles, journals and catalogs.